The police presence outside is permanent, and particularly sensitive to the arrival of foreigners. "We pressure this fucking multinational company from both sides," our comrade explained once we were safely upstairs, in the spacious meeting room overlooking the port. "At the container terminal our members fight on the job, and in the media we are running an anti-corruption campaign."

The union had recently succeeded in pressuring the government to direct the state-run anti-corruption taskforce to investigate Hutchison over their dodgy dealings with Indonesian government officials. The investigation was perhaps connected to the chief investigator of the anti-corruption body being splashed in the face with acid by an unknown assailant, leaving him blind in one eye. Our comrade discussed these events with a calm and confident tone: "We are not worried, the anti-corruption campaigns have great public support."

'Tenderising the bosses on the job before grilling them in the court or the paper' was a tactic described by BLF radicals in the late 70's and early 80's in Australia, and is still put to good use there by the best officials of the CFMMEU. Similarities between the tactics our Indonesian comrades apply in their struggles at the Port of Jakarta and our own experiences of union work in Australia are clues that can help to demystify the processes of accumulation that drive this latest phase of globalised capitalism.

An Italian comrade named Mario Tronti reminded us in the 1970's that "Thought is not needed to produce more thought, but to produce action. And action is conflictual." How can we use what here appears to be an increasingly homogenous experience of wage labour in Australia and Indonesia to build cross border organisations of workers, across multiple industries, that are capable of fighting the multinational corporations plundering both of those countries? Further investigation is required, and must take account of the unique historical circumstances that have shaped our Indonesian comrades' experience of struggle over and above obvious considerations like the continued capacity of the Indonesian ruling class to resort to more open forms of dictatorship in their repression of the workers' movement, or the complex role of political Islam in the world's largest majority Muslim country.

The Jakarta port union, or Serikat Pekerja Jakarta International Container Terminal (SPJICT), was established in 1999, one year after the toppling of the Suharto dictatorship. Bourgeois law in Indonesia mandates that unions are structured according to a shop or worksite-based model, similar to the system that prevails in the US. In order to extend their organising beyond the Jakarta port, the radical workers who built the SPJICT also set up the Federasi Pekerja Pelabuhan Indonesia (FPPI) in 2016, a federation now comprising 8 separate unions of dockers, seafarers, warehouse workers and nurses who work at port hospitals.

Our comrades in Jakarta explained that the radical politics practised by these organisations have their genesis in the dying days of the student movement against the Suharto dictatorship in the mid to late 90's. The anti-dictatorship struggle was hijacked by liberals who managed to distort the students' more radical demands into calls for a democratic pluralism that could be deployed in service of the nascent bourgeois parliamentary system - a familiar story. In the face of disillusion, many of the radical students who had been politicised by the struggle against dictatorship set about reasserting their demands for socialism upon entering the workforce, through newly constituted trade unions like the SPJICT. The real experience of organising under the open dictatorship of the bourgeoisie, as well as the harsh disillusions served up by the empty promises of liberal parliamentarism, has imbued this first generation of new Indonesian unionists with three outstanding characteristics that would be useful for Australian radicals to reflect on.

The first characteristic is our Jakarta comrades' realistic understanding of the limited capacity of bourgeois parliaments and elections to win and maintain radical gains for workers. The FPPI is not associated with, or affiliated to, any parliamentary party in Indonesia. During our stay in Jakarta, some representatives from the SPJICT were in fact participating in meetings involving a broad coalition of leftist forces that had come together with the goal of founding a radical socialist party. Socialist and Communist parties are still officially illegal in Indonesia, so much of the discussion revolved around neither succumbing to right opportunism (to not advance when the people are ready) nor left adventurism (to advance isolated from the people) in the extent to which the new party could openly demand socialism; right down to whether the word 'socialist' should be included in the new party's name. One comrade in particular from the SPJICT made a memorable and thoughtful contribution in his insistence that carrying out socialist work is more important than using socialist vocabulary, and the latter should be abandoned if, as the result of a period of state repression, it jeopardises the former. As that same comrade also explained, the emphasis on understanding the limits of bourgeois parliamentary politics for workers is not so that we can make a fetish out of our opposition to social democratic reformism (though its representatives often make that difficult). Rather, as the experience of our Jakarta comrades suggests, the absence of a direct association between the new Indonesian unions and any bourgeois parliamentary party means that the unions can much more easily and effectively develop an independent, class conscious workers' movement, a movement that is not distorted by either the dead-end of reformism or the superficial egoism of staffer-class, careerist politics.

This point relates to the second outstanding characteristic of the new Indonesian unionists: the genuine practice of solidarity that defines their methods of work, especially with regard to work within their own organisations. A corrosive but rarely discussed consequence of the almost total merger of personnel at the level of Trade Union Executive and ALP Factional Power Broker in Australia has surely been that the vulgar politics of individualism that defines the bourgeois parliamentary party has been imported into workers' organisations at almost every level. Instead of methods of work and relationships between comrades founded on a genuine and embracing sense of human solidarity, relationships that can be used as propaganda for socialism by providing a contrast to the shallow, self-serving values of capitalist culture, we see trade union leaders in Australia resorting to boasting, flattery, the pursuit of personal fame, and ridicule towards comrades in their day to day work. This is not the absence of some kind of 'real politics' within the labour movement, as has been fashionable to say, but rather the concrete presence of the politics of the bourgeois political party, which is itself a concentrated expression of the capitalist relationships of production that prevail in our society.

The dominance of this egoistic politics within workers' organisations has the effect of even further isolating the union leadership from its members, during a historical phase in which participation in unions is already greatly suppressed, because workers are reluctant to spend their precious time outside of work with people whom they cannot personally respect. This is not to say that there are no trade union leaders in Australia who lead by example through a genuine practice of solidarity in their work. The value of making these investigations lies in the opportunity for radicals to reflect on the processes that continue to hinder the construction of a revolutionary mass movement in Australia, and these processes are always bigger than any one individual. In this context, our movement could benefit significantly from reflecting on what allows our comrades at the Jakarta port to go about their union work with a spirit that strikes those who observe it as a living example of what human relationships could be in our glorious socialist future. How can we hope to inspire the masses back to the history-defining cause of their self-emancipation unless we uphold, through example, this kind of spirit in all of our work? Of course, we are not so naive as to believe that a few union officials being nicer to each other is all that is needed to bring about socialism in Australia. A further purpose of discussing these points is to explore the many different ways in which the parliamentary politics of the bourgeoise can disorganise the working class.

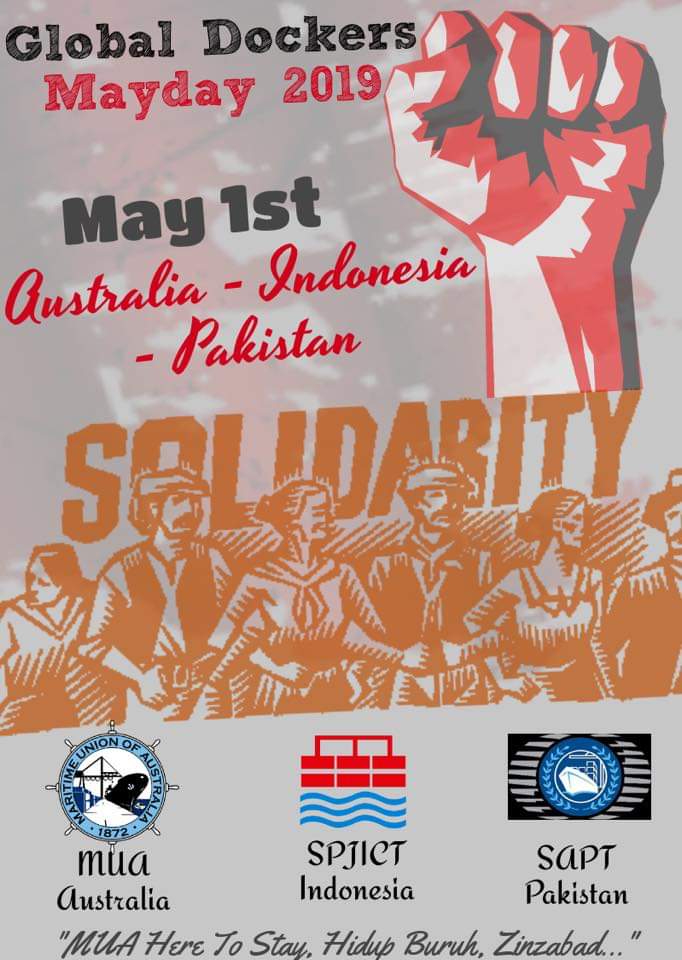

The third outstanding characteristic of the new Indonesian unionists is their internationalism. Comrades from the construction, transport and port unions organised an hours long meeting with us when the news arrived that unionists from a different country were visiting. They seemed to have an endless energy to discuss different experiences of work, of struggle and of strategies to beat the boss. On this point, the Sydney branch of our own MUA has done a splendid job of building cross-border organisations with comrades in the SPJICT. At the time of writing, port workers from Sydney, Jakarta and Karachi in Pakistan had organised a coordinated strike across three countries and two continents to commemorate May Day. This is exactly the kind of international organisation that our class needs if we are to stand up to the multinational corporations that are plundering the entire globe. Furthermore, in a country like Australia, where the masters and bosses have tried to use racism as a weapon to divide workers since the very beginning of European colonisation, a mass movement of the working class can be built only if we are able to foster the kind of internationalist class consciousness that defines our comrades in the SPJICT.

Every time workers share their experiences of work there is an opportunity to learn about our history, the shared history of the global working class. In the struggle to move from understanding history to making history, Marx's Capital is an invaluable weapon that can help us decipher the ways in which capital will subvert each of our victories to serve its expansion. A few months before our visit to the Jakarta port, the bosses at Hutchison replaced 400 union dock workers from the SPJICT with scab labourers engaged on temporary contracts.

The struggle to win those jobs back continues. With their thorough understanding of that other truth once identified by BLF radicals at the highpoint of their historic struggle - 'you won't get from the court what you can't hold at the gate' - our comrades in Jakarta will surely prevail.

Antonio G. 8 May 2019

Antonio G. 8 May 2019