VANGUARD - Expressing the viewpoint of the Communist Party of Australia (Marxist-Leninist)

For National Independence and Socialism • www.cpaml.org

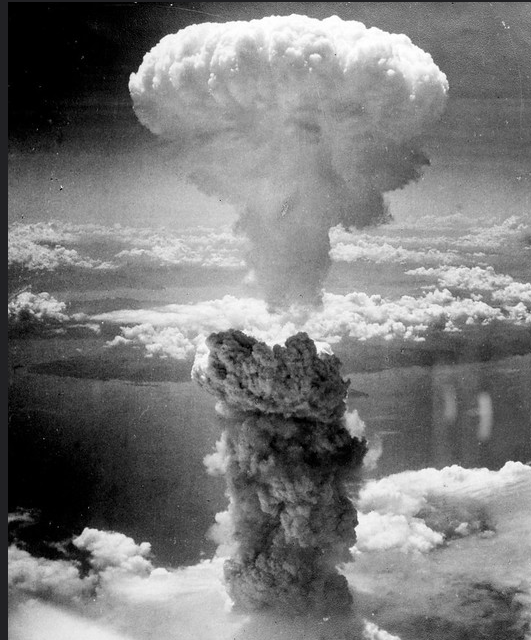

(Above: Nagasaki, August 9, 1945)

On December 9, an influential Australian media commentator and presenter made a comment which revealed her ignorance of the political struggles that surrounded the defeat of Japanese militarism at the end of World War 2.

Specifically, she was unaware of the entry of the Soviet Union into the war against Japan, and the relationship of that to the dropping of the atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

In a sense, it is not her fault. The narrative that has been built up around the US use of atomic bombs is tightly controlled, dominates academia, school curricula and the media. It simply “disappears” any view sympathetic to the Soviet Union or questioning of the US narrative.

Stalin secures his eastern front

The attempts by the Soviet Union under its Foreign Minister Maxim Litvinov, during the 1930s, to win acceptance of collective security as a defence against fascist aggression, were rebuffed by the British and French who sought to direct the Nazis eastwards against the Soviet state.

The Stalin leadership expected a German attack, and had fought several battles against the Japanese between 1932 and 1939 along the border between Japanese-occupied Manchuria and Mongolia and the Soviet Union. The Soviet-Mongolian victory over the Japanese in the Battles of Khalkhin Gol in 1939 convinced the Japanese to concentrate on expanding into China rather than continuing their conflicts with the Soviets.

Japan and the Soviet Union signed the Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact on 13 April 1941, allowing Stalin to withdraw troops from the east and concentrate his defences on the west, facing Germany. The famous German spy, Richard Sorge, who worked as a journalist in Japan at this time, provided Stalin in mid-September 1941 with documentary proof that Japan would abide by the Treaty and not attack the Soviet Union.

At the Tehran Conference in November 1943, Joseph Stalin agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan once Germany was defeated.

At the Yalta Conference in February 1945, Stalin agreed to Allied pleas to enter the war against Japan within three months of the end of the war in Europe.

The Soviet intention was to make a unilateral declaration of war against Japan on August 7, 1945.

US bombs Japan to keep Soviets out

In the lead-up to that date, the US imperialists were working frantically to develop the horrifying new weapon, the atom bomb.

If they could develop the bomb in time, they could force a Japanese surrender before the Soviets won control of Japan’s second biggest island, Hokkaido, as was the plan. They were desperate to avoid the power-sharing arrangement that had been imposed on Germany at the war’s end.

James Forrestal, then US Secretary of the Navy, writing of James Byrne, who had been appointed President Truman’s Secretary of State on July 3, 1945, said “Byrnes said he was most anxious to get the Japanese affair over with before the Russians got in…” (Forrestal Diaries p. 78).

This was spelled out by Norman Cousins and Thomas K. Finletter in an article in 1946. Finletter later became Truman’s Secretary for Air. The article said, that in dropping the bomb, “the purpose was to knock out Japan before Russia came in – or at least before Russia could make anything other than a token of participation prior to a Japanese collapse.” (Saturday Review of Literature, June 15, 1946).

Scientists who created Bomb opposed its use on civilians

The atomic scientists who developed the bomb were vigorously opposed to its use on Japan. These scientists had thought long and deeply about the problems of atomic warfare and its implications and had appointed a committee to present their views to the US Secretary of War, Henry L Stimson. Accordingly, a month before the test of the bomb in New Mexico, a company of seven scientists, headed by Professor James Franck, submitted a report.

This report has also become known as the Franck Report, and its main purpose was to advise against use of the bomb on Japan.

Richard Flanagan’s latest book, Question 7, has the great credit of bringing to the fore the little-known Hungarian Jew and nuclear scientist Leo Szilard who was one of the originators of nuclear fusion.

He was also one of the seven signatories to the Franck Report (The Franck Report: A Report to the Secretary of War, June 1945 (fas.org) ) who stated to the US Secretary of War in June 1945 that they believed “the use of nuclear bombs for an early unannounced attack against Japan inadvisable”, and called for “an effective international control of nuclear armaments”.

Szilard was active on other fronts. I quote Flanagan (p. 137):

Szilard’s torment was only beginning. In late May, weeks before the first atomic bomb was tested in New Mexico on 16 July he passed a memorandum to James Byrne, soon to be secretary of state for the new president, Harry Truman, for him to deliver to Truman. Szilard asked that the president withhold his approval of using the bomb against Japan, pleading that Japan be given advance warning, arguing for a demonstration bomb explosion to be witnessed by Japanese officials to show the terrifying power that the US could now unleash.

Byrnes never delivered the memorandum.

The day after the first atomic bomb test Szilard, frightened by what he had been central in creating, forwarded a petition to Truman signed by 155 Manhattan Project scientists that advanced a moral argument against the bomb’s use against Japan, warning that any subsequent global nuclear confrontation would be catastrophic. There would have been more signatories but J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of Los Alamos, forbade the petition’s circulation there.

General Groves delayed the petition’s delivery. To negate its impact he ordered a poll of his scientists only to discover that 83 per cent supported a demonstration of the bomb to Japanese officials before using it. He buried these findings also.

US war crimes to defeat Japan and freeze out the Soviet Union.

In the later narratives of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the anti-Soviet element disappeared, and justification centered on the desire to avoid the deaths of US troops in the island-hopping approach to Japan.

The two atom bombs certainly hastened the Japanese surrender and saved US military losses. But the targeting of the civilians of Hiroshima and Nagasaki (and of the conventional bombing of Tokyo before this) was a war crime, that is, the killing of civilians to save military lives.

And the US knew from having cracked Japanese encryption codes, that its emperor Hirohito was close to surrendering anyway. His change of heart had been prompted by the US air war on the civilian population of Tokyo.

The Japanese capital had been within reach of US bombers since February 1945, when its bombing of Kobe and Tokyo began.

The decisive bombing raid was on March 9-10, 1945 when 1,665 tons of bombs rained down on 16 square miles of Tokyo, killing 100,000 civilians and leaving one million homeless. It was the single most destructive bombing raid of the war. However, it required 279 B-29 Superfortresses to carry and drop this combined payload. Although the subsequent bombing of Hiroshima was not quite as destructive, it required only one plane and one bomb.

US President Truman authorised the dropping of an atom bomb on Hiroshima on August 6, one day before the Soviet Union declared war on Japan. A second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki two days after the Soviet entry into the war in the light of swift and devastating Soviet advances into Japanese-occupied Manchuria and Korea.

This is the buried truth of the US war crime of using atom bombs against civilians to “keep out the Soviets”.

It should not be forgotten.