VANGUARD - Expressing the viewpoint of the Communist Party of Australia (Marxist-Leninist)

For National Independence and Socialism • www.cpaml.org

The Anti-labour Party administration is holding a Productivity gabfest in Canberra 19-21 August. Humphrey McQueen sets ‘productivity’ as a driver for the structured dynamics of how the exploitation of every wage-slave must be intensified if the rule of capital is to persist.

Productivity: of what? from whom? for whom?

The drive for so-called productivity raises a central aspect of Marxism, namely, surplus-value. Militants need to understand the ramifications of that key to capitalism if we are to push back the current offensives.

Labour-time

To win the battle of ideas in the latest contest over productivity, we should go back to what WorkChoices aimed to do for the expansion of capital. The ALP and most unions ran the line that WorkChoices combined a nasty man and wrong thinking with a fondness for wage-cuts. Howard remains a nasty liar. However, his policies were more than another personality defect. Nor was he driven by bad ideas. Every social practice carries an ideological aspect. Neo-liberalism, for example, was more than a bad idea in the heads of nasty people. Like WorkChoices, it expressed the needs of capital, which is why we branded it WorstChoices. The needs of capital go beyond cutting wages.

Neo-liberalism was a splendid idea for most sectors of global capital. Like Keynesianism and Monetarism, its days were numbered. How next to serve the interests of rival corporates, and their supporting nation-market-states, is being hammered out in Trump’s trade-wars.

WorkChoices was about the disciplining of labour-time. Capital buys our labour-power in units of labour-time. The productivity of capital is measured by how much value the boss-class can extract from those units. Capital, therefore, drives up the rate of output per unit of labour-time that it subsumes as variable-capital. Managers do this through intensifying the discipline over us as their wage-slaves who embody the capacity to add value.

Capitalists struggle to get rid of every obstacle to their freedom to have value added at any hour and under any condition. Even weak unions are a brake on the rate of exploitation of our labour. Hence, WorkChoices set out to universalize ABNs and individual contracts as barriers to our collective strength.

Firms stand down workers without pay if there is a break in the reproduction or circulation of surplus-value. Bosses want to be free to call us in for random and/or broken shifts. That control over hours delivers a double advantage to capital. First, it pays for our labour-power only when we wage-slaves are adding value. Secondly, the uncertainty of shifts bullies unorganized employees into doing whatever they are told for fear of not getting enough shifts to eke out a living. The bosses lie that flexibility makes life easier for single mums.

Wages

On average, the personifications of capital pay us in full for the socially-necessary costs of reproducing our labour-power. That is what bosses mean by a fair day’s pay. Of course, they battle to keep all the value that is surplus to that amount. On top of enduring exploitation in spite of an equal exchange, workers know only too well how much swindling goes on. In practice, the bosses do everything they can to pay below that socially-necessary average. They will not pay super or penalty rates unless we are organised enough to force them. Here is one of the reasons why WorstChoices set out to disorganize working-people.

Of course, firms would rather pay us no wage at all, but then they would have no living-labour to exploit or buyers for those producing consumer goods, and, in the longer term, no orders would be placed with the firms that make the machines on which we make both kinds of commodities.

Capitals are not just involved in a race to the bottom on wages. There is no point in paying a dollar a day for one pair of shoes if a worker with a machine can make ten pairs in an hour. The low-wage factories, here and abroad, combine longer hours, more intense discipline and hazardous conditions. Factory disasters in Bangladesh are driven by deadlines for foreign orders. Deadlines indeed!

The rate of our exploitation is not measured by wage-scales. A skilled worker on $130,000 a year can deliver more surplus-value than a peasant trained to snap parts together. Hence, the best-rewarded employees can be more exploited than the worst paid.

Absolute surplus-value

Two ways to extend the length of the working-day are unpaid overtime and abolishing smokos. Bosses are also notorious for owning clocks which run fast in the morning and slow in the afternoon. Women at call centers in the U.S. of A. are forced to wear diapers instead of going to the lavatory. Stepping up exploitation by a longer day is becoming more pervasive now with mobiles, i-pads and home computers which keep workers on call 24/7.

Capital increases its take of surplus-value by extending the number of hours we work. Its owners can benefit even if these extra hours are paid for at overtime rates. This is possible because equipment is not idle and so the overhead for each unit of output is lowered. Best of all for capital is unpaid overtime, and there is plenty of that.

The greater the value of the plant, the more pressures on the agents of capital never to let it stand idle. Mining is a prime example, with twelve-hour shifts. Computer-controlled equipment sees RioTinto operating around the clock in the Pilbara.

Relative surplus-value

At the same time, the agents of capital try to extract more surplus-value during the standard hours. They strive to do this through piece-rates, speed-ups, and bullying.

Occupational health and safety fall victim to productivity drives. Through speed-ups, capital passes the cost onto the worker through injury and death. The law backs them up. As Marx puts it: killing is not murder when done for profit. Year in and year out, supermarket-chains drive truckies to drugs and death to meet delivery schedules. Rio is pushing to cut sick-leave entitlements from forty-five to fifteen days a year.

Because capitalists install machines to extract more surplus-value, they invest in new technologies if they promise to lift the rate of exploitation, or to ward off rivals. The bosses favour innovation only when it protects profit. Labourers with picks and shovels produced as much surplus-value as the driver of a front-end loader when those navvies were on the dole in the 1930s.

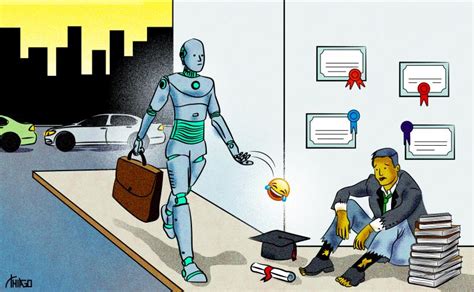

‘Your prize for saving time at work with AI is more work,’ declares a headline in The Wall Street Journal, July 7, 2025. Who ‘owns’ the time saved? Labour or capital? The answer depends on whether we are working for wages, or are on piece-rates. If we have exchanged timed units of our labour-power for an agreed wage, all the time saved still belongs to the buyer of our capacities to add value. If you are on piece-rates, the time is yours. The catch is that the agents of capital will force down the price they pay per unit so that you will need to work longer to take home the same weekly income. By wages or by piece? Same difference.

Accumulation

Under the rule of capital, the only way to add value is through our exploitation to fund expansion. To do so, the personifications of capital first have to exploit labour to extract surplus-value; secondly, their agents have to sell the goods and services we supply so that as much surplus-value as possible can be realised as profit; thirdly, they have to invest much of that profit in resources for reproduction to hold off competitors. Only then can capital go on to extract ever more surplus-value. … and so on …. until the next crisis.

Profit-taking is not an end in itself, just as exploitation is but one step towards the expansion of capital. ‘Accumulate! Accumulate!’ Marx writes. ‘That is Moses and the Prophets.’ A capitalist who puts self-indulgence above re-investment soon ceases to be a capitalist.

Marx explains how money-capital goes into the production of commodities, which must be sold to secure a greater sum of money-capital to re-invest. The most important component in these new commodities is that they carry more value than went into their production. That extra comes from our labour.

Market-value

If productivity is down, how is it that the ASX is going gang-busters through all previous records? And why is that happening if price/earning ratios on shares are also through the roof?

When capitalists are not rabbiting on about ‘productivity’ as if it were a universal good, they babble about ‘adding value’, blurring the one into the other. Accountants have long grappled with how to put a monetary value on businesses. One rule is to deduct liabilities from assets. But what counts as an asset? Should auditors embrace goodwill and brand recognition? If so, how to put a number of those intangibles? Nowadays, they are paid to accept whatever a corporation’s Chief Information and Financial Officers claim their ‘values’ are, and paint the bullseye around the arrow.

Piero Sraffa’s 1926 “The Laws of Return under Competitive Conditions” pondered how to measure the value of capital? In terms of its profit? If so, how to measure profit? If it is measured as a percentage of the value of capital, the process is circular. The professoriate abandoned attempts to resolve the paradox. Economics undergrads will never hear of Sraffa’s article, and most of their lecturers won’t have either. Ignorance is bliss.

Upon the announcement of China’s Deepseek in late January, the media reported that billions had been wiped off NVIDIA’s value with. Most of those billions never existed, but were one form of fictitious capital. Such figures are arrived at by multiplying the price of the last share traded by the total number of shares. Speculators erect Babel Towers of marked cards.

No sector in recent capitalism has been more innovative in this regard than finance. Yet, the world’s most successful investor, Warren Buffett, refused to buy into derivatives or collateralized-debt obligations because he could not understand them. The crash of 2007-8 suggests that traders did not understand them either. What they did understand was they had invented new ways to collar cash without going through the tiresome and risky business of making and selling commodities. Most of these financial instruments are parasitical on the capitalists engaged in exploiting us directly do so.

And so are all rent-takers, of whom two-dollar Rinehart is the exemplar. Until recently, she did not exploit mine-workers directly. Instead, she had lived off the rents that Rio paid her for the whack of leases nicked by her father from his partner Peter Wright. She had been unproductive in the worst sense.

Producing barbarism

Under capitalism, even the most destructive enterprises are deemed productive so long as they add surplus-value. Wars and drugs are prime examples.

It is easy to see how war is productive of profit for individual corporations from Haliburton to Boeing. But war can also be productive for the whole capitalist system. The biggest example is how military expenditures kicked the U.S. out of its 1930s deflationary cycle.

Drugs also benefit more than Big Pharma. Western imperialists used opium in the nineteenth-century as a weapon against the Chinese people to open China up to unequal ‘free-trade’ treaties. Today’s drug trade is productive of profit with cocaine and heroin just other commodities, like Coca-Cola and Holden cars. In addition, more drug money goes through the banks and other casinos than governments ever confiscate as the proceeds of crime.

Producing communism

Within capitalism, unproductive labour is morally superior to productive labour since the latter is grounded on exploitation. Under communism, all labour will become unproductive in the sense that there will no longer be exploitation.

Communists raise tough questions about productivity: what kind of society is produced? We draw a line between what is productive under the rule of capital and what should be produced to serve the needs of working people. For capital, productivity means the addition of surplus-value. Workers struggle to produce a world without the want, the wars and the waste that capitalism over-produces.

Boosting ‘productivity’ under capitalism has landed the world with a super-abundance of material goods. Their over-production plunders the wealth of nature, leaving mountains of garbage and oceans polluted with islands of plastic waste.

Surplus-value comes from the collective efforts of working people everywhere. Hence, no individual is responsible for all of the value that he or she adds. A lone craftsperson depends on workers in transport and power supply. Under socialism, all workers will be paid the full cost of reproducing our labour power. Some of that reward will come to us as money-wages. The closer we move towards communism, the more of our needs will be supplied as social goods, such as free public-transport, education, health and housing.

When communists speak of boosting productivity, we hold to a vision about the kind of society that we can build together. Our collective efforts promise to enrich individual creativity, protect the wealth of nature, and meet our collective needs. Engels explained the part played by labour in the transition from ape to man. Putting the highest social value onto the productivity of social labour will make us more human.

Appendix on the Productivity Commission