Dancing in the Snow: The Paris Commune as a Paradigm for Social Change?

Written by: (Contributed) on 9 September 2021

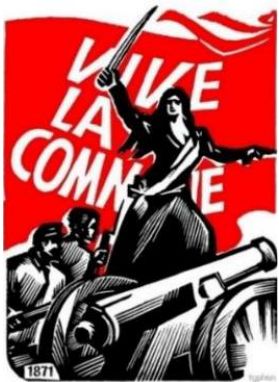

In August this year in Adelaide a historian gave a presentation at a public gathering on the Paris Commune to acknowledge its 150th anniversary. The speaker stated the focus of the talk is, "...essentially about its lessons: what it can tell us about today’s struggles, what it can say about our socialist future." It was a very lengthy and comprehensive outline of the Communards 2-month struggle in the French Spring of 1871. Consequently, this post will be an abridged presentation, presenting 3 of the speaker's 7 lessons and a very interesting introductory historical anecdote. Readers will appreciate some of these little-known facts spoken about by the speaker. A Party document covering the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune can be found here. . The full text of the historian’s presentation can be found here:

In August this year in Adelaide a historian gave a presentation at a public gathering on the Paris Commune to acknowledge its 150th anniversary. The speaker stated the focus of the talk is, "...essentially about its lessons: what it can tell us about today’s struggles, what it can say about our socialist future." It was a very lengthy and comprehensive outline of the Communards 2-month struggle in the French Spring of 1871. Consequently, this post will be an abridged presentation, presenting 3 of the speaker's 7 lessons and a very interesting introductory historical anecdote. Readers will appreciate some of these little-known facts spoken about by the speaker. A Party document covering the 150th anniversary of the Paris Commune can be found here. . The full text of the historian’s presentation can be found here:

..........................

INTRODUCTION

Imagine this: a cold winter’s day in January 1918, on the 73rd day of the Soviet Republic, Vladimir Lenin leaves his office in the Smolny Institute in Petrograd and, in the surrounding park, he astonishes everyone by… dancing in the snow. Lenin dancing! We know why: he was celebrating the fact that the Soviets had surpassed the duration of the Paris Commune by one day.

This wasn’t the first event to commemorate the Commune, but it’s one of the most famous.

LESSON 1 REVOLUTIONARY TACTICS

The first lesson is to be realistic about the nature of revolution, or indeed any radical social change programme. You know many of these things already but they are worth repeating:

That it is crises that coalesce different movements. After 150 years this is common knowledge, but the Commune reminds us to be vigilant and exploit crises to push for change.

That you must never underestimate the capacity for terrorism by liberal regimes. When you take on the liberal state, class interests will be paramount. The liberal state is strong and can be vicious; it can and will strike back with unparalleled savagery against those people who get in its way. Class interests will of course hide behind proclamations of ‘order’, ‘morality’, ‘human rights’; but if the state is threatened the best you can hope for is a strike of capital (Australia 1972-75, France 1981-83); at worst you risk the bloody fate of the Commune. Some may find this difficult to accept; I refer those to Domenico Losurdo’s Liberalism: A Counter History (2005, 2011), now translated into English.

That you mustn’t avoid direct military operations. In a civil war it is not enough to maintain power like the Communards did; you have to extend it. The Commune’s first success was on 18 March when they prevented the Versaillais from taking away their cannons away. But this became a source of passivity: the cannons were saved; the enemy had fled to Versailles; wasn’t that sufficient? No, it wasn’t! Instead of quickly launching a resolute offensive to complement its victory in Paris, it tarried, prevaricated, debated, and gave the Versailles government time to prepare for the blood-soaked week of May. Communards effectively held power in their hands but weren’t sure what to do with it, permitting the enemy to regain its breath and re-establish its position.

LESSON 6 WOMEN

This is actually the most interesting aspect of the Commune: the crucial role of women and women’s issues: The Communards were ‘nobodies’. They were mocked for it: ‘Look at this stonemason who wants to govern France!’, said one Versaillais soldier about a Communard worker he was about to execute. And the mockery became contempt when these ‘nobodies’ were women. First of all because, in 1871, women wielded little power and had few independent rights, and in the case of working class women, were the unseen in public life.

You know the deal: politics was seen through the through the prism of masculinity, so women challenging the patriarchal order could only be seen in derogatory terms. Women were viragoes, harpies, harridans; and as one Versailles conservative put it: a Communard woman was by definition ‘a hysterical bitch in need of a good fuck!’. How things don’t change!

Yet women in the Commune were the most active in forming committees. They took their part in its defence standing shoulder to shoulder with the men. They played a crucial role in shaping its policies and fought vigorously for the ability to participate equally in its political life. The working class in France in 1871 was well on the way to dechristianisation, and working women were the most hostile to the Church and its priests who’d been complicit in past oppression, so it’s little wonder that women’s committees were strongly anti-clerical and took over Church buildings where they sermonised the new political order from its pulpits. The famous Communard, Louise Michel, reports how women were ‘more capable than the men to say definitively that is has to be this way.’

The main points here are:

One, that women’s issues are central to any programme of social transformation and the two cannot be separated in either theory or practice. Changing gender relations and reforming the role of women and the family are not add-ons and cannot be postponed to ‘after the revolution’; rather they need to be imbricated in the process of social change itself. By now we should be familiar with this lesson, but it’s still overlooked by the masculine ethos of the left. The Communards knew this in 1871! More than the men, the women of the Commune transgressed social expectations and struggled for a form of communal life founded on solidarity and gender equality in Paris and beyond.

And two, equally important, is to let women, (on indeed any ‘minorities’) discover their own solutions. This occurred in the Commune and resulted in the formation of (female) networks in local communities that became conduits for the politicization of Parisian women. On this topic I cannot exaggerate the importance of the memoirs of the Communard Louise Michel, who was also a model for that other great revolutionary feminist, Alexandra Kollontai in the 1920s.

LESSON 7 SOCIALISM AS ‘A FESTIVAL OF THE OPPRESSED’

I was going to outline some lessons of the Commune regarding fraternity or, as one writer put it , socialism as ‘a festival of the oppressed’. I’ll just make a few short remarks.

The Commune undertook some acts of great symbolic meaning. One was the burning of guillotine, on 6 Apr 1871, at the Place Voltaire, as both a statement against the barbarism of a judicial system based on punishment and a reference to the Enlightenment tradition of which the Commune felt a part. Another was the demolition of the Vendôme column on 15 May 1871 (near the Opera and facing the Ritz Hotel, made up of the cannons from the Battle of Austerlitz and with a statue of Napoleon on top), as a symbol of the barbarity of war and Napoleonic imperialism. Marx had actually predicted this event in 1852 and the painter Gustave Courbet made it his mission. He succeeded but it cost him very dearly during the repression – however, that’s another story.

Others were experiments with some new forms of social and public life , such as opening up public spaces, usually reserved for the well-to-do, to the working class, or allowing free access to the museums of Paris, or holding concerts indoors and in parks for public causes.

Such things gave a different ambiance to the closeted exclusivity of privilege and wealth. They are no mean achievements in themselves, but when combined with the political and social innovations they show a new vision of communal life and solidarity.

Print Version - new window Email article

-----

Go back

Independence from Imperialism

People's Rights & Liberties

Community and Environment

Marxism Today

International

Articles

| Have I improved enough yet? Teaching and the labour process. |

| Support HungryPanda delivery riders’ campaign for wages and conditions. |

| Health workers force Victorian government backdown |

| Boss Class Agenda or an Independent Working Class Agenda? |

| Workers united struggle under re-elected ALP government is needed |

| Workers’ struggle as a class gives life to ACTU's "strength in numbers, power in solidarity, we are unstoppable" |

| Farm Numbers Down - Farm Debt Up |

| Building struggle around an independent working class agenda is the key |

| Labor hire warehouse workers and government support service workers win through struggle |

| Vale Ron Owens |

| Tasmanian potato growers spitting chips |

| Workers are revolting despite restrictions on strike action |

| "Productivity" for workers means job losses and higher workloads |

| Forewarned is forearmed: Economic Reform Roundtable |

| Public sector workers take on SA government |

| Courts uphold government attack on militant union |

| Support BAE shipworkers’ action for same job, same pay |

| Labor Sweeps to Power: Now It’s Time to Deliver for Workers |

| Dystopia and the Sacrosanct Elephant |

| Workers Strike at PepsiCo's Snack Foods Factory - An Example of The Leading Class In Action |

-----