Marxism Today: The unfairness of a “fair day’s pay”

Written by: on

It has been the catchcry of the official trade union movement worldwide for 200 years. It’s a slogan so often heard in the labour movement that it is almost a cliché. Now we are told Australian workers have lost it and that we need to “change the rules” to get it back. It is of course “a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work”.

On the surface, this seems like a reasonable demand. As workers we all have to work to survive and want to be suitably compensated for the work that we do. But when we take a closer look at workers’ wages and bosses’ profits and where they come from, a “fair day’s pay” just doesn’t seem as fair anymore.

What are wages?

As workers under capitalism, we have only one thing that allows us to survive – our ability or capacity to labour. That ability to labour, like almost everything under capitalism, is a commodity that is bought and sold. Karl Marx called it our ‘labour power’. We have to sell our labour power to a boss in exchange for a wage.

A wage is really the price the boss pays to use your labour power for a certain amount of time i.e. a shift at work - maybe 4 hours, maybe 8 hours, maybe more or less. So, what determines your wage? Or in other words, what determines the price of your labour power?

Like all commodities, labour power has a value. Like all commodities, that value is determined by the average time and cost it takes to produce it. Since our labour power is inseparable from ourselves as living human beings, the cost of producing and reproducing our labour power is the cost required to keep us alive and functioning as workers for our entire life. This includes things like food, housing, clothes, transport, education etc. In other words, the basic cost of living. It also includes the cost of maintaining and raising our families and kids. The kids replace us as workers when we die, ensuring a supply of labour for the bosses well into the future.

What makes up the basket of basic necessities needed to reproduce our labour power varies with the time, place, history and societal customs of where we live. For example, in Australia in 2019 it is fairly common for a family to need two cars, owning your own home by the time you retire is a pretty standard expectation, mobile phones are a necessity to work and function socially. All these things make up our basic living costs and so must be factored in when calculating the value of our labour power and therefore our wage. In comparison, a worker in a developing country will have lower basic living costs and so will require a different basket of basic necessities, and in turn, require a lower wage to live as a worker in their country.

But there’s still a little more to it. At any given time and place, there are several important factors that impact exactly what your wage might be. One is the supply and demand of qualified workers in a given industry or field. The more workers available to do the job the lower your wage is likely to be, and vice versa. Another very important factor is the existence or non-existence of strong trade unions.

Unions reduce competition between individual workers and gives them the ability to force the boss to pay higher wages. In short, at any particular point in time, wages are determined by the relative strengths of the working class and the capitalist class in the marketplace. When the working class is in a strong position wages will tend to be higher, and when the capitalists are in a stronger position wages will tend to be lower.

But while wages may be higher or lower at any particular point in time and place, as a rule they will fluctuate around the value of our labour power as determined by the costs of the basket of basic necessities as described above. This rule applies to the working class in general, and not to any individual worker as such. This explains why it is that some workers may be a bit better off and some a bit worse off, but why it is impossible for the working class generally to ever become rich just from working.

What are profits?

Now that we understand wages, we can turn to the question of profits. When we sell our labour power to the boss, we agree to work for a certain amount of time in exchange for a wage that basically meets our cost of living, or in other words, is equal to the value of our labour power. For arguments sake, let’s say you are lucky enough to work full time in an ice-cream factory 8 hours a day, 5 days a week and receive a wage of $1,500 which you can live comfortably enough on. Presumably a fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work.

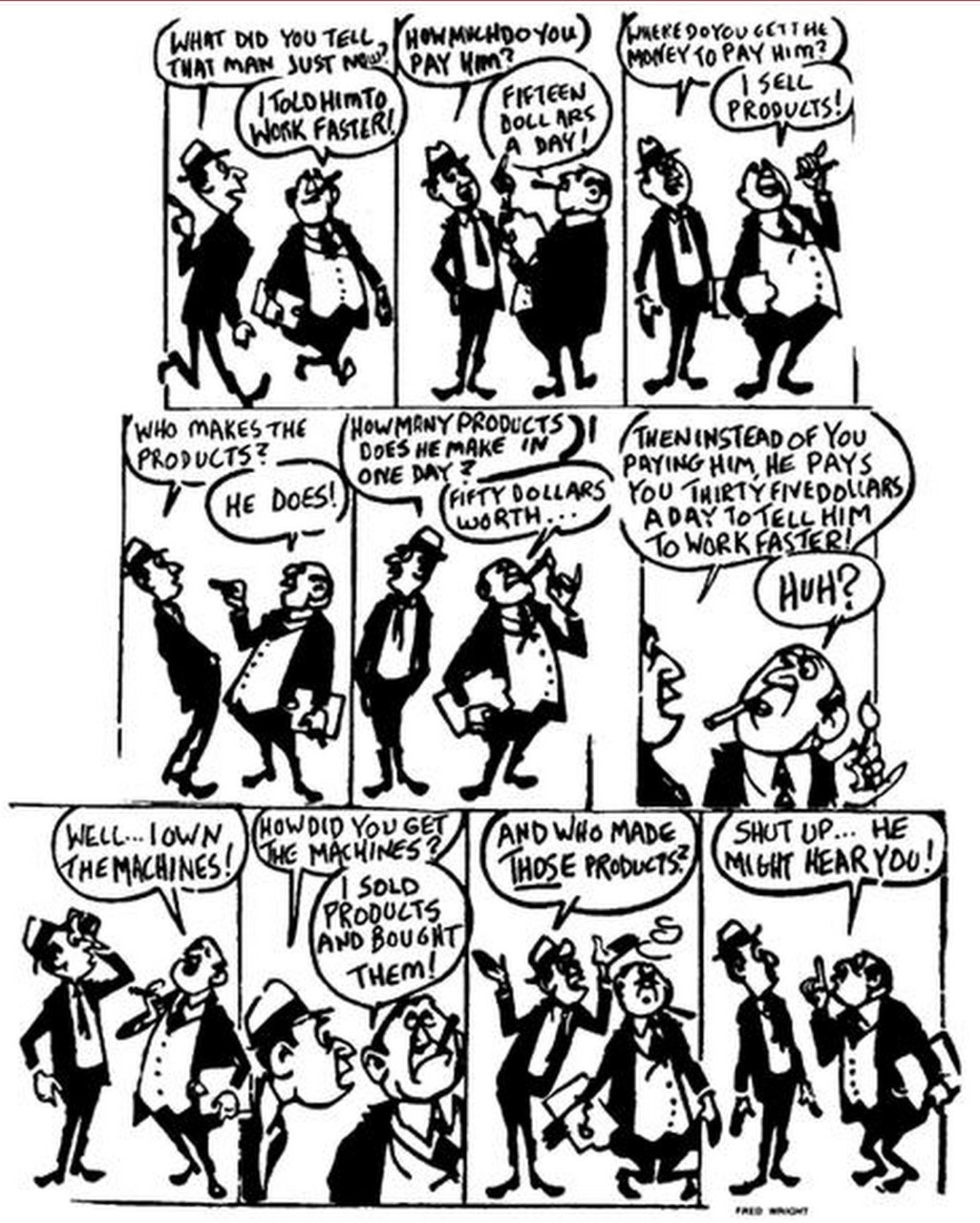

But, let’s say that over the course of the working week you make ice-cream valued at $2,500. Regardless, you still only get paid $1,500. So, what about the $1,000 difference? Well that’s value that you created by working but don’t get paid for. Karl Marx called it ‘surplus value’. Once all the ice-cream you produced is sold, the boss pockets your surplus value as his profit.

As workers we produce all the value in society, but we only receive a portion of it back in the form of wages. The bosses take the rest as profits. How’s that for fair?

But what about…

But what if the ice-cream workers at the factory got together and demanded to be paid the full $2,500? Wouldn’t that be fair then? Well the boss would certainly be faced with a dilemma. If he agreed to pay it and kept everything else as it was before, then there wouldn’t be any surplus value and hence no profit. Bankruptcy could result which would mean that there would be no money to keep the ice-cream factory operating.

So, to stay in business the boss would be forced to come up with a way to extract surplus value from the workers to make a profit. In other words, the workers would need to produce even more ice-cream in the same amount of time. Perhaps by making the workers work harder, or with some new machines that can make ice-cream faster. Either way, the result is that workers would be producing value that they aren’t paid for (surplus value) and the boss would be pocketing the profit. Fair?

Can we change the rules for fairness?

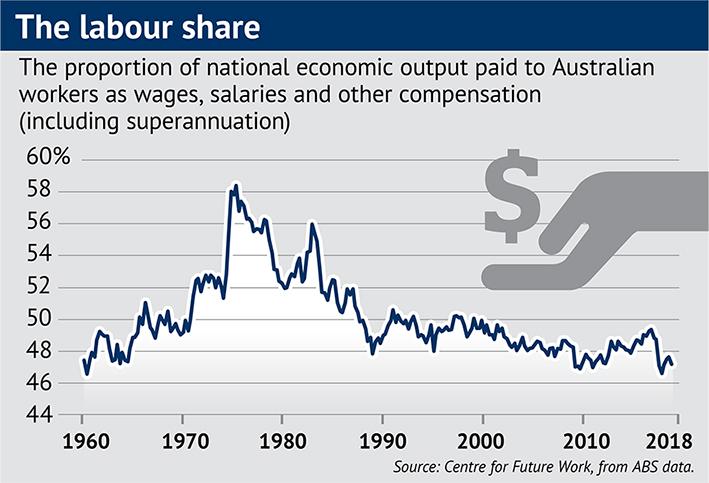

The Australia Institute released a report in 2018 detailing the long-term decline of the labour share of Australia’s GDP. The report reveals the economic output in the Australian economy and how much of that output goes to paying workers. It was found that in March 2018, 47.1% of GDP went to workers incomes. That’s about 11% less than the historic high of 58.4% in 1975. And close to the lowest at any point in the last 70 years. This decline has been mirrored by a rise in the share going to corporate profits, which are once again nearing record highs after falling from their peak in the global financial crisis in 2008/9.

The Australia Institute released a report in 2018 detailing the long-term decline of the labour share of Australia’s GDP. The report reveals the economic output in the Australian economy and how much of that output goes to paying workers. It was found that in March 2018, 47.1% of GDP went to workers incomes. That’s about 11% less than the historic high of 58.4% in 1975. And close to the lowest at any point in the last 70 years. This decline has been mirrored by a rise in the share going to corporate profits, which are once again nearing record highs after falling from their peak in the global financial crisis in 2008/9.

This trend is a reflection of the diminished strength of the trade union movement. Trade union strength has steadily declined since the introduction of neo-liberalism and the restructuring of Australia’s economy starting in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Draconian anti-union laws restrict the ability of workers to fight for wage increases, while companies are given free rein to make as much profit as they see fit.

All of this means that Australia is experiencing some of the greatest inequality that it has ever seen. Profits are soaring and wages are declining. And the industrial laws are keeping it that way. It is this reality that provides fertile ground for the ACTU’s campaign to ‘change the rules’.

The campaign aims to change the rules to allow workers and unions to reverse the trend. It speaks of restoring balance and returning fairness to the system. But while it’s obvious that the system is less fair now than what it was in 1975, is it right to say that it was ever fair? To what point do the labour share and profit share of GDP have to get to make the system fair? If wages rose 11% and profits declined 11% would we have a “fair day’s pay” again?

The revolutionary alternative

The Marxist explanation of wages and profits outlined above shows that it is the workers producing value that they don’t get paid for which is the source of the bosses’ profits. No matter how high workers wages may be, as long as the boss is making a profit it means the workers are being exploited. Hence, there can never be a “fair day’s pay” under capitalism.

The trade union demand of a “fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work” blinds workers to the reality of the capitalist system. It misleads us into thinking that fairness for the workers can be achieved under capitalism. Indeed, this is the role of the trade unions under capitalism. They are great organisations for the defence of workers’ rights and wages against the bosses and must be supported, but ultimately, they confine workers’ struggle within the bounds of capitalism rather than for its revolutionary overthrow.

The bosses or capitalist class are like parasites that live off the unpaid labour of workers. They are redundant. The working class must overthrow them and start to rule society for themselves in a socialist system. Then the surplus value that workers produce would belong, not to the parasitic bosses, but to the working class as a whole, held in common to meet the needs of the great majority of the people. Only then can we ever really start to speak of a “fair day’s pay”.

Print Version - new window Email article

-----

Go back

Independence from Imperialism

People's Rights & Liberties

Community and Environment

Marxism Today

International

Articles

| Adventurist Class War Rejecting the Working Class |

| Productivity: of what? from whom? for whom? |

| More on Imperialism and Religion |

| Imperialists used religion to justify their actions |

| Building a New Socialist Society |

| The “three constantly read articles” should still be constantly read. |

| Two new publications to promote study and guide practice |

| Reply to a reader |

| Criticising Xi Jinping Thought |

| BOOK REVIEW---CULTURE IS NOT AN INDUSTRY |

| CPA (M-L) concludes 16th Congress |

| Study of Marxism-Leninism is the key to understanding the role of the ALP and unions |

| The Bezosmoth |

| Book Review: SLOW DOWN |

| Book Review: VULTURE CAPITALISM |

| Multipolarism – the new Kautskyism |

| Celebrating the 60th anniversary of Australia’s oldest revolutionary newspaper. |

| E.F. Hill’s “The Labor Party?” republished. |

| Report on the Australian political situation to the ICOR Asia Conference 22-23 July 2023 |

| “Australian” companies that serve foreign capital |

-----